A haboob, or dust storm, blowing into Ahwatukee, near Phoenix, as seen from the top of South Mountain, looking south on July 23, 2011. Inhalation of a fungus found in soils of the U.S. Southwest is what causes Valley fever. After an event like this, incidences of infection tend to spike.

Some folks who’ve lived in the Southwest for years—digging in spiny gardens, walking dogs in the wash, chipping through desert caliche to add a backyard wall or deck onto the house, and waiting on the side of Interstate-10, blinkers flashing during a haboob (or dust storm)—may think the mild symptoms of Valley fever they suffered were the flu.

A tourist visits over the holidays, goes for a hike in a nearby canyon, golfs at a local resort and joins the crowds at Gates Pass in Tucson or South Mountain in Phoenix for a saguaro-filled sunset. He or she heads home and falls deathly ill from the respiratory illness known as coccidioidomycosis, or cocci, that sneaks into their bloodstream and attacks their central nervous system.

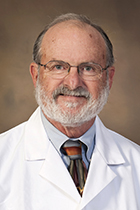

The director of the University of Arizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence, John N. Galgiani, MD, a professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases, has won a $2.27 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), a unit of the National Institutes of Health, to study the immuno-genetic underpinnings of why.

The director of the University of Arizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence, John N. Galgiani, MD, a professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases, has won a $2.27 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), a unit of the National Institutes of Health, to study the immuno-genetic underpinnings of why.

Why are some barely affected by Valley fever while others admitted to intensive care?

“The gist of it is that people get different kinds of severity for Valley fever. Some have no problem. Others die of it. We think it has to do with their immune response and differences in genetics behind those,” Dr. Galgiani said.

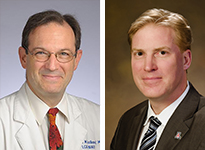

With co-investigators (pictured left) Steve M. Holland, MD, and Yves A. Lussier, MD, he’ll be probing what makes some more susceptible for the infection to spread from their lungs, causing what’s known as “disseminated coccidioidomycosis.” This is when the infection gets in the blood and moves from the lungs to skin, bones and joints, and/or the spinal cord and brain.

With co-investigators (pictured left) Steve M. Holland, MD, and Yves A. Lussier, MD, he’ll be probing what makes some more susceptible for the infection to spread from their lungs, causing what’s known as “disseminated coccidioidomycosis.” This is when the infection gets in the blood and moves from the lungs to skin, bones and joints, and/or the spinal cord and brain.

Dr. Holland is NIAID’s director of the Division of Intramural Research and serves as chief of the Immunopathogenesis Section within its Laboratory of Clinical Infectious Diseases. He has been a co-author with Dr. Galgiani on a number of papers related to immuno-genetic studies on Valley fever.

A UA professor of medicine and statistics, Dr. Lussier is associate vice president and director of the Center for Biomedical Informatics and Biostatistics at the UA Health Sciences as well as associate director of the UA BIO5 Institute and of cancer informatics/precision health at the UA Cancer Center. He’s the big data expert able to decipher DNA sequencing to tease out answers others might not see.

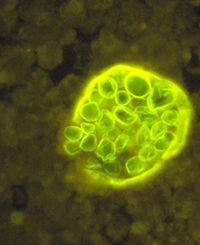

A spherule of Coccidioides immitis (right), the fungus that causes Valley fever, with endospores spreading outward.

A spherule of Coccidioides immitis (right), the fungus that causes Valley fever, with endospores spreading outward.

About 60 percent of those who come into contact with the fungus Coccidoides that causes Valley fever—found in soils of the U.S. Southwest, parts of Mexico, and Central and South America—don’t have any symptoms, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About 5-10 percent develop serious or long-term problems in their lungs. For about 1 percent, the infection spreads to other parts of the body. Of roughly 150,000 cases reported a year, Valley fever kills about 160 people.

Dr. Galgiani’s and Holland’s latest article—“Risk Factors for Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis, United States,” in the February issue of the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases—notes race/ethnicity, sex, pregnancy and immune status are critical factors to the potential severity of Valley fever infection.

In a literature review that included 370 cases of disseminated cocci over the period 1975-2014, they found an immunosuppressed person (due to age or health) was 30-50 percent more likely to suffer from spread of the infection. Dissemination to the central nervous system was reported in 37 percent of pregnant women infected, a third of whom died—three-quarters of those in the third trimester. At 59 percent of all such cases, whites were more likely to suffer nervous system attacks (Asians, 38 percent; blacks/Hispanics, 13 percent). Males made up 84 percent of multisite infection cases, with the number of blacks double any other race. Osteomyelitis, or infections reaching the bone, also was more common among minorities (blacks, 82 percent; Hispanics, 69 percent; Asians, 60 percent; whites, 29 percent).

An X-ray from the CDC of a man with disseminated cocci in his lungs. For additional images, click here.

An X-ray from the CDC of a man with disseminated cocci in his lungs. For additional images, click here.

In several patients, Drs. Galgiani and Lussier note, a gene mutation was identified by Dr. Holland that’s an indicator for susceptibility to the serious form of Valley fever. In a follow-up collaboration, Drs. Galgiani and Holland frequently identified possibly deleterious mutations in similarly affected patients. This could provide a clue as to what more subtle genetic differences might commonly be responsible for disseminated cocci.

“Taken together, these discoveries have raised the possibility that disseminated cocci is a consequence of defects or delays in early recognition and response following infection. If this hypothesis is correct, it opens up the very exciting possibility that a preventative vaccine might be effective against subsequent infection, even in some or most persons genetically susceptible to disseminated cocci,” Dr. Galgiani said.

This project permits investigators at the NIH and at the University of Arizona to work together, utilizing unique resources of each institution. Findings from these studies may provide new tests to determine which persons are at risk of serious disease if they contract Valley Fever. They may also help in the development of preventative vaccines.

All of these things are coming together at an opportune time for the UA Valley Fever Center for Excellence, Dr. Galgiani said. Fariba M. Donovan, MD, PhD, a new physician recruited from Intercoastal Medical Group in Bradenton, Fla., starts April 10 with her time split between research for the center and work with the Division of Infectious Diseases. She earned her medical degree at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences and did residency training at Tehran University of Medical Sciences, both in Iran; and completed an internship at Bethesda North Hospital and residency in internal medicine at Good Samaritan Hospital, both in Cincinnati, Ohio, as well as an infectious diseases fellowship at Tampa’s University of South Florida. She also earned a doctorate from Gifu University School of Medicine, in Japan, and conducted genetic studies of the Valley Fever fungus.

All of these things are coming together at an opportune time for the UA Valley Fever Center for Excellence, Dr. Galgiani said. Fariba M. Donovan, MD, PhD, a new physician recruited from Intercoastal Medical Group in Bradenton, Fla., starts April 10 with her time split between research for the center and work with the Division of Infectious Diseases. She earned her medical degree at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences and did residency training at Tehran University of Medical Sciences, both in Iran; and completed an internship at Bethesda North Hospital and residency in internal medicine at Good Samaritan Hospital, both in Cincinnati, Ohio, as well as an infectious diseases fellowship at Tampa’s University of South Florida. She also earned a doctorate from Gifu University School of Medicine, in Japan, and conducted genetic studies of the Valley Fever fungus.

In addition, the UA College of Medicine – Tucson and UA Foundation have established an annual endowment for research at the center based on money remaining in the Farness Fund for Valley Fever and Allied Fungal Diseases, established with a $1 million donation by the family of Orin J. Farness, MD, a Tucson physician who recorded the first case of culture-confirmed coccidioidomycosis in 1938. The center hosts the annual Farness Lecture, now in its 22nd year, in honor of Dr. Farness every November as part of Valley Fever Awareness Week in Arizona.

Dr. Galgiani’s project, “Immuno-Genetic Basis for Human Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis” (supported by the NIAID under Award No. U01AI122275), runs through February 2021.

EXTRA INFO

- For more information on Valley fever, visit the UA Valley Fever Center for Excellence website redesigned in 2016: vfce.arizona.edu

- Media can also find a plethora of informational and multimedia resources at this website highlighting “UA Expertise on Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis)” created by UA News and the UA Department of Medicine.

ALSO SEE:

“Annual Farness, Founders Lectures Focus on Fungal Diseases, Medical Imaging” | Posted Nov. 16, 2016

"UA Researchers Closer Than Ever to Valley Fever Vaccine" | Posted Oct. 27, 2016

“Valley Fever Research, Vaccine Gain Congressional Attention in Phoenix” | Posted Oct. 18, 2016

“New National Guidelines for Valley Fever Treatment Led by UAHS Center Director” | Posted July 29, 2016