Stefano Guerra, MD, PhD, MPH, a professor of medicine in the UA Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine (PACCS), won a $3.6 million award last fall from the National Institutes of Health to investigate how better regulation of a protein found in lung cells might impact persistence of asthma in an individual as they shift from childhood to adult.

Stefano Guerra, MD, PhD, MPH, a professor of medicine in the UA Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine (PACCS), won a $3.6 million award last fall from the National Institutes of Health to investigate how better regulation of a protein found in lung cells might impact persistence of asthma in an individual as they shift from childhood to adult.

The five-year grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), an NIH unit, will be used to study the protein known as CC16, which is a biomarker of lung epithelial cell injury and viewed as a protective mediator in the airway inflammatory process. The protein is secreted mainly by club cells, also known as bronchiolar exocrine cells, in distal airways of the lungs but can be measured in blood circulation.

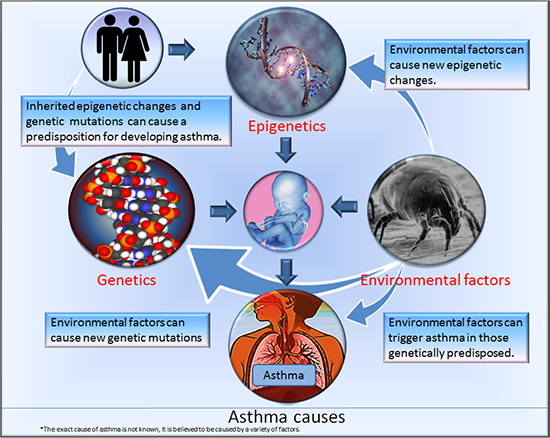

Causes of asthma illustrated (Source: Wikipedia/ 7mike5000): An asthma attack makes lung airways get smaller and too much mucous to be generated. This makes it hard to breathe. Causes of attacks can be environmental, such as pollen pictured above, epigenetic or genetic.

Causes of asthma illustrated (Source: Wikipedia/ 7mike5000): An asthma attack makes lung airways get smaller and too much mucous to be generated. This makes it hard to breathe. Causes of attacks can be environmental, such as pollen pictured above, epigenetic or genetic.

Dr. Guerra, principal investigator (PI) on the NIAID grant, is also the Henry E. Dahlberg Chair in Asthma Research at the UA College of Medicine – Tucson, population science director with the UA Health Sciences Asthma and Airway Disease Research Center (A2DRC), an associate professor with the UA Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, and a UA BIO5 Institute member.

Co-investigators include Tara Carr, MD, Julie Ledford, PhD, and Monica Kraft, MD, from the UA Department of Medicine; Marilyn Halonen, PhD, professor emerita, UA Department of Pharmacology; Fernando Martinez, MD, A2DRC director; and Duane Sherrill, PhD, professor emeritus, Epidemiology and Biostatistics Division, UA Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, and a leading expert in longitudinal modeling of pulmonary data.

The project establishes an international consortium among some of the world’s leading research cohorts on asthma that provide unique data on “thousands of participants followed from birth well into their adult life,” Dr. Guerra said.

These include the Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study, launched in 1980 by the Arizona Respiratory Center (now A2DRC), and Sweden’s BAMSE and the United Kingdom’s Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study (MAAS). Each involve longitudinal research with observation of participating patients over decades.

These include the Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study, launched in 1980 by the Arizona Respiratory Center (now A2DRC), and Sweden’s BAMSE and the United Kingdom’s Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study (MAAS). Each involve longitudinal research with observation of participating patients over decades.

Animation (right) showing lung constriction in asthma attack (Source: Wikipedia/7mike5000)

Cohort participants will be characterized to evaluate the hypothesis that individuals with CC16 deficits are at increased risk for persistence of childhood asthma, Dr. Guerra said. The team also will test if protective effects of CC16 are mediated by responses to asthma pathogens by studying how nasal epithelial cells to be collected from cohort participants respond to Mycoplasma pneumoniae, a bacterium that causes respiratory infections particularly among patients with asthma.

Cohort participants will be characterized to evaluate the hypothesis that individuals with CC16 deficits are at increased risk for persistence of childhood asthma, Dr. Guerra said. The team also will test if protective effects of CC16 are mediated by responses to asthma pathogens by studying how nasal epithelial cells to be collected from cohort participants respond to Mycoplasma pneumoniae, a bacterium that causes respiratory infections particularly among patients with asthma.

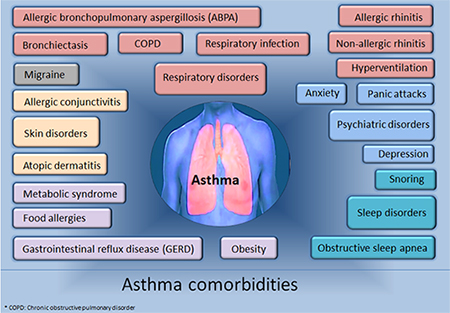

Comorbidities that can complicate an asthma patients life (Source: Wikipedia/7mike5000)

“Ultimately, our objective is to establish the value of CC16 as a protective factor from persistence of asthma and evaluate its possible use in risk stratification and novel therapeutic interventions,” Dr. Guerra added.

For more on Dr. Guerra’s research, read the following Q&A:

Q: Which other research cohorts are involved in this study?

A: This project includes the three birth cohorts of the Tucson CRS, the Swedish BAMSE, and the UK MAAS studies. These studies provide extensive phenotypic data and large bio-repositories from three independent and geographically diverse cohorts. Most importantly, they are among the few ongoing asthma studies that have followed participants from birth into their adult life.

Q: Are you trying to halt that progression, i.e., stop or remedy asthma’s persistence into adulthood?

A: That is our long-term goal. We focus on persistence of childhood asthma into adult life because these persistent forms of the disease have been conclusively linked to development of chronic lung function deficits and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in adult life. At the present time, however, there are neither established prediction models nor available biomarkers for early risk stratification of long-term sequelae of the disease.

Q: What types of “novel therapeutic interventions” might be involved?

A: Should these studies support a direct causal role of CC16 deficits in persistent asthma, the next step would be to evaluate CC16 augmentation as a therapeutic intervention in this disease, by either administering the human recombinant CC16 protein or molecules that increase endogenous production of CC16. For example, we have recently reported (American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine) that retinoids increase CC16 secretion by human bronchial epithelial cells and vitamin A treatment results in a significant increase of serum CC16 levels.

Q: I would imagine you’re looking at a precision medicine approach to those interventions – can you elaborate?

A: There are at least two ways in which results from this project could inform precision medicine approaches in asthma. First, results from these studies could identify a subgroup of children who are at high risk for persistent disease and should receive tailored interventions. Second, findings from this project could point towards patients with established deficits in circulating CC16 as a potential target population for interventions aimed at CC16 augmentation.

Q: What role will some of the co-investigators play in this study?

A: This study will definitely be a team effort:

- Drs. Ledford and Kraft will lead all experiments on nasal epithelial cells collected from participants from the three cohorts.

- Dr. Martinez will advise in all epidemiological and clinical studies

- Drs. Halonen and Carr will direct the CC16 assays

- Dr. Sherrill will lead longitudinal statistical analyses

- Dr. Erik Melén, an environmental epidemiologist with Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet, and Dr. Angela Simpson, with the North West Lung Centre of England’s University Hospital of South Manchester, are the PIs of the two international cohorts of BAMSE and MAAS, respectively, and co-investigators on this study as well.

Q: How does your approach with CC16 differ from other research approaches at the UA or beyond regarding the “search for a cure for asthma”?

A: This project is focused on a key protein and its role in persistent asthma. Although the biological functions of CC16 have not been conclusively elucidated, growing epidemiological and experimental evidence, to which our group has substantially contributed, indicates that this protein exerts protective properties against airway inflammation and the development of lung disease. At the UA, we have several ongoing projects that are targeting the mechanisms of action of CC16 and its potential use in the prevention and personalized treatment for three of the most debilitating lung diseases: COPD, chronic asthma, and cystic fibrosis.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a unit of the National Institutes of Health, under grant number 1R01AI135108-01.

ALSO SEE:

“$3.6M NIH Grant to UA-Led International Research Consortium Seeks Precision Medicine Solutions to Stopping Asthma in Childhood” | Posted Jan. 23, 2018

“Four from DOM among Promotions Announcements at College of Medicine General Faculty Meeting, Nov. 16” | Posted Nov. 14, 2017

“Positive Airway Pressure Therapy Could Reduce Hospitalizations for COPD Patients, says UA Study” | Posted Aug. 7, 2017